Moshfegh gives the old canard about the association between artistic genius and madness an additional twist to arrive at the notion that inventing complex stories about the intersecting lives of entirely imaginary people is itself a species of madness. It’s the amused contemplation of that void that gives rise to the dark exhilaration of her work-its wayward beauty, its comedy, and its horror. Like a surgeon, or a serial killer, Moshfegh flenses her characters, and her readers, until all that’s left is a void. it’s a haunting meditation on the nature and meaning of art. Moshfegh knows that when human company is swept away, a baroque inner life can often flourish, and Vesta’s increasingly monstrous inner life grows to occlude her view of the world. Moshfegh has toyed with this technique in much of her work. The unreliable narrator, as a technique, appeals to novelists who are interested in the gaps (tragic, comic) that yawn between how we conceive of ourselves and how the world perceives us to be. But creating this sort of narrative tension isn’t quite what Moshfegh is up to-or, rather, it’s only a fraction of what she's up to. Vesta’s unreliability is flagged so thoroughly in the early pages that you begin to suspect that Moshfegh is playing some kind of higher-order game with narrative tension.

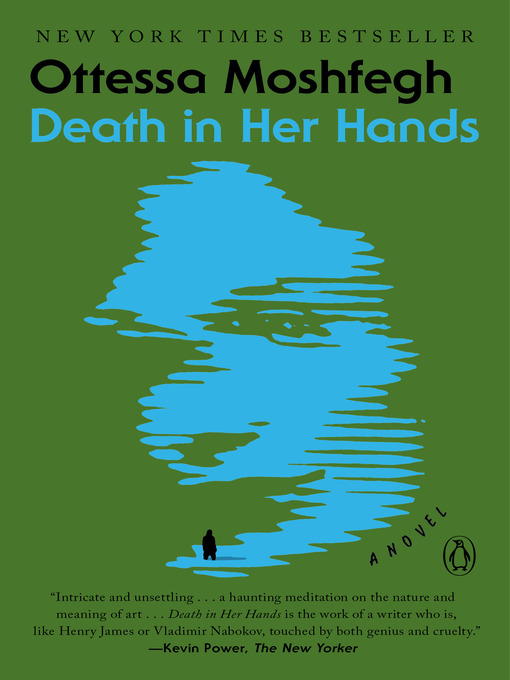

But it makes no real secret of its tricksiness-which is in itself grounds for mistrust. Death in Her Hands is another tricksy novel. Vesta’s speculations are every bit as vivid as Eileen’s. Death in Her Hands, Ottessa Moshfegh’s intricate and unsettling new novel, appears at first to occupy familiar territory.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)